The Shifting Locus of Authoritative Advice for Gen-Z and Their Financial Lives: An Opportunity for the Credit Union Sector?

Gen Z are reshaping the way financial advice is sought and acted upon. Moving away from traditional sources like family, banks, and financial advisors, younger generations are turning to social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram, where financial influencers —“finfluencers”— offer accessible, though often unregulated, advice.

While this shift has democratized financial education, it has also introduced significant risks to advice-seekers, including misinformation, high-risk investment recommendations, and a lack of regulatory oversight.

For Credit Unions, this transformation presents challenges and opportunities. Younger audiences often see traditional financial institutions such as banks as outdated, inaccessible, and misaligned with their values. However, Credit Unions, with their ethical foundations and community focus, are well- positioned to fill the trust gap created by the shortcomings of both traditional institutions and finfluencers.

By engaging with young people where they seek advice – on social media – Credit Unions can offer relatable, trustworthy, and sound financial guidance that aligns with their mission to promote financial literacy and inclusivity.

This white paper explores ways in which Credit Unions can respond to this shift in advice-seeking behaviour to revitalise and grow their memberships. Discussions with UK-based Credit Unions reveal cautious optimism about engaging in the finfluencer space, with several recognizing the potential to use social media platforms to amplify messages of fairness, community, and responsible financial management. However, barriers such as limited digital innovation capacity, regulatory concerns, and a general lack of awareness about the finfluencer phenomenon remain.

To address these challenges, we propose a coordinated approach for Credit Unions to build capacity and credibility in the digital advice ecosystem. This includes developing sectoral guidelines for engaging responsibly with finfluencers, pooling resources to experiment with digital campaigns, creating a practical playbook for social media engagement, and modernizing product offerings to align with Gen Z’s preferences for fast, convenient, and values-driven services.

By strategically entering the online advice ecosystem, Credit Unions can not only mitigate the risks of misinformation but also position themselves as a trusted alternative to both traditional institutions and unregulated finfluencers. This approach offers a pathway for Credit Unions to expand their membership, strengthen their community impact, and secure their relevance in an increasingly digital world.

Authorised Push Payment Fraud Mitigation: The Role of Data and Information Sharing

Authorised Push Payment (APP) fraud has been increasingly steadily, with many of the common types originating on social media and the internet. Combatting and mitigating APP fraud will require cooperation across financial institutions and tech and telecoms companies, with data and information sharing playing a key role. Recent UK legislation aims to facilitate data and information sharing to combat fraud and privacy enhancing technologies (PETs) provide technical solutions to enable better understanding and widespread sharing of fraud intelligence that enable data protection and privacy.

Mapping ESRS Disclosure Datapoints to Relevant Datasets

The integration of geospatial data into sustainability reporting frameworks addresses challenges related to inconsistent and outdated Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) information. This third white paper from the Financial Regulation Innovation Laboratory (FRIL) explores the application of geospatial data in enhancing the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). By aligning geospatial datasets with specific ESRS disclosure requirements, the study provides a foundation for corporations conducting double materiality assessments, auditors validating disclosures, and third parties—such as financial institutions and environmental organisations—performing due diligence.

Geospatial data can be applied at the asset level (e.g., factories) or aggregated using a bottom-up approach linked to financial ownership, improving transparency and comparability across companies, sectors, and regions. However, the study finds that only 7% of ESRS datapoints can be externally validated due to the dependence on proprietary company information. Despite this limitation, different stakeholders benefit from distinct datapoints: investors may prioritise datapoints linked to external risks such as flooding or greenhouse gas emissions, while water-focused non-governmental organisations may emphasise hydrological indicators.

The EU Omnibus package (February 2025) introduces significant changes to ESRS and corporate sustainability reporting. These include a reduction in in-scope companies (80% fewer under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive), limited value chain coverage, and fewer required datapoints, which may lead to a data gap and reduced transparency. However, the shift towards quantitative over qualitative datapoints presents a critical opportunity for geospatial data to bridge this gap, offering independent, real-time, and scalable insights for ESG reporting.

Furthermore, the revision of assurance requirements under the Omnibus package raises concerns about data verification and reporting accuracy. Given these regulatory shifts, integrating satellite- derived data into sustainability reporting frameworks could enhance objectivity, comparability, and reliability. Future regulations should embed geospatial data as a core element to strengthen the integrity and effectiveness of sustainability disclosures in the EU and beyond.

Generative AI for Simplified ESG Reporting in Financial Services

We demonstrate the potential for Generative AI to simplify Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reporting in financial services. Banking and financial institutions are required to comply with ever more stringent and demanding ESG related compliance requirements. A lack of mandatory, universally enforceable sustainable finance standards and guidelines makes effective ESG reporting across industries and countries difficult for financial institutions.

Vast amounts of data processing are required, spanning structured quantitative numerical data and unstructured qualitative textual data. Generative AI has the potential to deliver an innovative solution to this ESG reporting challenge through identifiable capabilities in decision support, including document summarisation; data visualisation; individual and multiple company analytics; and customised report generation. Furthermore, several technical features allow organisations to customise Generative AI systems to meet bespoke business requirements and information technology constraints.

These technical features include response speed and agility; multiple version choice and algorithmic support; user friendly interfaces; scalability and upgradability. In the use case demonstration, we show how a Large Language Model (LLM) can be used to generate responses to a set of common analyst questions pertaining to ESG using single and multiple annual report sources.

This use case brings to life the potential for Generative AI in simplifying compliance in respect of ESG reporting. We then bring together LLM and cutting-edge large Vision Model (LVM) capability to move from text-based prompting to verbal-based prompting for the ESG reporting exercise. We show that this integrated language-vision approach leads to enhancements in performance compared to a sole LLM approach. Indeed, we demonstrate that placing emphasis on key words within the verbal prompts generates more targeted responses from the LLM.

Consumers as Innovators and the UK Financial Conduct Authority’s Consumer Duty

We address the scope, purpose, and initial implementation from July 2023 of the UK Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA) Consumer Duty. As an instance of financial regulation innovation, the Consumer Duty is having a major impact in the financial services sector and has impacted on the organisation of markets for financial services and in the interactions of consumers and providers.

The Duty brings to prominence the ways in which the production, marketing and use of financial services products and services are strongly interrelated. It highlights: (1) Consumers’ financial literacy; (2) Providers’ confidence that their products and services and communications about these are being understood; and (3) How providers are anticipating and coping with vulnerability among their customers.

Together, these recognise consumers as being active, engaged, adaptive and innovative. We position the paper in terms of active consumption and market and marketing channels so as to focus on active consumers, and consumer vulnerability. To illustrate how the Consumer Duty is shaping the development, marketing and uses of financial services, we explore a sample of cases reported by the Financial Ombudsman Service, in which the issues referenced are akin to the elements addressed in the Consumer Duty.

We find that consumer understanding is a prominent factor, which also impacts on a number of other categories and subcategories. We also see, through the perspective of Consumer Duty, a somewhat pacified or pacifying view of consumers and in some instances, tensions emerging between consumer adaptations and the contractual terms for financial products and services. This adds to our conceptual framing of market channel and its implications for consumer vulnerability.

Navigating Double Materiality in ESG: Practical Steps for Businesses

Introduction to Double Materiality

Double materiality emerged as a concept relatively recently, but has been gaining interest as a practical, actionable conceptualization of ESG outputs. Materiality itself traditionally focused on how a factor impacted firm financial performance, a decidedly unidirectional approach. Double materiality looks to identify both the financial materiality of an issue as well as the impact materiality, which assess the material impact upon society and the environment. Rising stakeholder demands and regulatory pressures are making double materiality more and more prevalent in today’s business climate. To practically navigate double materiality, companies must adopt comprehensive strategies that integrate both financial and societal/environmental dimensions into their decision-making processes.

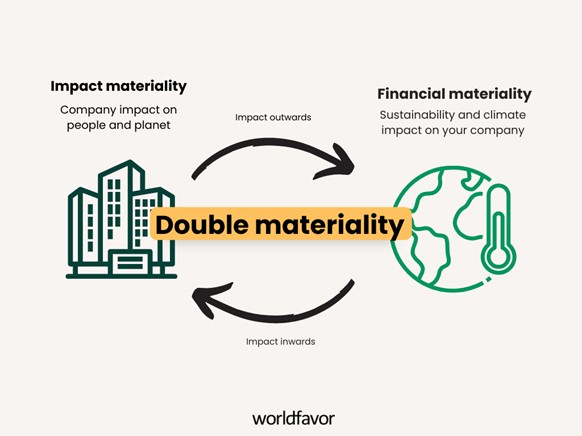

The EU Commission’s Supplementary Directive 2013/34/EU states, “…double materiality as the basis for sustainability disclosures”. The two dimensions of double materiality, impact and financial, are further noted as being ‘…inter-related and the interdependencies between these two dimensions shall be considered” (section 3.3). This is best visualized in the following graphic:

Image credits: Worldfavor, July 2023

As shown, the assessment impact or financial materiality are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. The impacts are, from a company perspective, split between impact inwards and impact outwards, meaning the materiality of an issue as it impacts the company itself (impact inwards) and the material impact of a company’s actions on society and the environment (impact outwards). In today’s reporting climate, those two directions are seen as more closely related than ever before.

In industries such as Aerospace, the concept of materiality is closely linked to innovation. Companies like SpaceX, Orbex, or Collins Aerospace have defined themselves as organisations with a sustainability element. This is a clear demonstration of the circular nature of double materiality, in that the impact materiality (the firm’s sustainability efforts) are directly impacting the financial materiality (inwards impact in the form of sales and customers, outwards impact in the form of environmental innovation and positive social investment) and vice versa. For instance, when discussing potential environmental impacts of manufacturing for aerospace and defense technologies, S&P Global argued that the climate transition would be significantly material for stakeholders as manufacturing and transportation emissions require long-term strategic planning but is less likely to impact near-term credit (S&P Global, 2022).

In defining impacts, it is important to note that risk and opportunities are both components of impact, but that they are not necessarily the entirety of the impact. For instance, an environmental impact may become financially material due to changing weather patterns. Conversely, a financial issue may develop impact materiality through a change in regulations or soft law pressures.

Practical Steps for Businesses

To effectively navigate double materiality, businesses need to implement a series of practical steps, encompassing governance, stakeholder engagement, data collection, and reporting.

1. Establish Strong Governance Frameworks

Leadership and Oversight: Establish a governance framework that includes oversight by the board of directors or a dedicated ESG committee. This structure should ensure that double materiality is integrated into the company’s strategic objectives.

Roles and Responsibilities: Clearly define roles and responsibilities for ESG initiatives across various departments, with a defined company-wide strategy to ensure efficiency of data collection and reporting. Assign senior executives to oversee both financial and impact materiality aspects, ensuring alignment with the company’s overall strategy.

2. Engage Stakeholders

Identifying Stakeholders: Identify and actively engage with key stakeholders, including investors, employees, customers, suppliers, regulators, and local communities. Understanding their concerns and expectations is vital for addressing both financial and impact materiality.

Dialogue and Collaboration: Engage in open and continuous dialogue with stakeholders through surveys, meetings, and advisory panels. Collaboration with stakeholders helps in identifying material ESG issues that are relevant from both financial and impact perspectives.

3. Conduct Materiality Assessments

Materiality Matrix: Develop a materiality matrix that plots ESG issues based on their importance to stakeholders (impact materiality) and their potential financial impact on the company (financial materiality). This visual tool helps prioritize ESG issues that require attention.

Dynamic Assessments: Conduct regular materiality assessments to adapt to evolving ESG landscapes and stakeholder expectations. This ensures that the company remains responsive to new challenges and opportunities.

4. Integrate ESG into Risk Management

Risk Identification: Identify ESG-related risks that could affect the company’s financial performance and societal impact. This includes environmental risks (e.g., climate change), social risks (e.g., labor practices), and governance risks (e.g., corruption).

Risk Mitigation: Develop and implement strategies to mitigate identified risks. This might involve adopting sustainable practices, improving supply chain transparency, or enhancing corporate governance standards.

5. Develop Robust Data Collection and Reporting Mechanisms

Data Collection Systems: Implement robust data collection systems to gather accurate and reliable ESG data. Use technology solutions like IoT, blockchain, and AI to enhance data accuracy and transparency.

Reporting Standards: Align reporting with established frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), and Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). These frameworks provide guidelines for comprehensive and comparable ESG reporting.

Integrated Reporting: Consider adopting integrated reporting, which combines financial and ESG information into a single report. This approach provides a holistic view of the company’s performance and its impacts, enhancing transparency and accountability.

6. Foster a Culture of Sustainability

Employee Engagement: Educate and engage employees at all levels about the importance of double materiality and sustainable practices. Encourage employees to contribute ideas and initiatives that promote sustainability.

Incentives and Recognition: Establish incentive programs to reward employees for their contributions to ESG goals. Recognize and celebrate achievements in sustainability to reinforce the company’s commitment to double materiality.

Challenges and Solutions

Data Complexity

In speaking to any ESG practitioner, one of the first challenges to arise is data collection. The data itself is often spread throughout a company, does not fit neatly into easily-organised spreadsheets, or may be difficult to understand in differing contexts (i.e. data from suppliers regarding their carbon emissions may not be shared in the format required by reporting standards).

To address this, companies can invest in advanced data management tools, third party support or automation systems, and design internal systems for data collection. It will be an investment of time and personnel but is also likely to be regulated and required in the near future.

Stakeholder Alignment

Particularly in industries with heavy manufacturing or extractive practices, it may be difficult to align stakeholder interests in a manner that is socially and environmentally material, without sacrificing financial performance. Engaging with stakeholders and third-party expertise while seeking innovative solutions and long-term strategic planning allows companies to effectively address ESG concerns.

Conclusion

Navigating double materiality requires a strategic and integrated approach that aligns financial performance with societal and environmental impacts. By establishing robust governance frameworks, actively engaging stakeholders, conducting dynamic materiality assessments, integrating ESG into risk management, developing comprehensive reporting mechanisms, and fostering a culture of sustainability, companies can effectively integrate double materiality. Success in this area not only enhances corporate reputation and stakeholder trust but also drives long-term value creation in an increasingly sustainability-focused world.

Resources

Boeke, E., York, B. N., London, D. M., Tsocanos, B., York, N., & Paris, P. G. (2022). Sustainable Finance Credit Ratings ESG Materiality Map Aerospace And Defense.

Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772 of 31 July 2023 supplementing Directive 2013/34/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards sustainability reporting standards, (2023).

Sean Michael Kerner. (2024, April). Double Materiality. Https://Www.Techtarget.Com/Whatis/Definition/Double-Materiality#:~:Text=Double%20materiality%20acknowledges%20risks%20and,Environment%20and%20society%20at%20large.

S&P Global. (n.d.). Materiality Mapping: Providing Insights Into The Relative Materiality Of ESG Factors https://www.spglobal.com/esg/insights/featured/special-editorial/materiality-mapping-providing-insights-into-the-relative-materiality-of-esg-factors

Worldfavor. (2023, July). CSRD: what is the double materiality assessment? Https://Blog.Worldfavor.Com/Csrd-What-Is-the-Double-Materiality-Assessment.

Erika Anderson’s work has focused on ESG and sustainability in the tech and finance space for the better part of a decade. In working closely with industry partners, she focuses primarily on issues of sustainable finance, social and environmental intersections, and actionable research for strategic ESG implementation. She also serves as Co-Founder of the Guam Human Rights Initiative, a collaborative research nonprofit focused on human rights issues on Guam and throughout the Pacific.

A Guide for MiCA sustainability disclosures for cryptoassets

Scottish Fintech Company, Zumo wrote a very detailed guide on the implications of the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MICA) and its sustainability disclosure requirements for the crypto industry. The central idea is that MICA’s new regulations will significantly impact how cryptoassets are reported, particularly concerning their environmental sustainability.

Key takeaways from the article begin by explaining;

- The MICA framework, established by the European Union, aimed at creating a unified regulatory environment for cryptoassets. This regulation addresses issues such as market integrity, consumer protection, and the environmental impact of digital currencies.

- MICA mandates that cryptoasset service providers must disclose detailed information about the sustainability of their operations. This includes the energy consumption and carbon footprint associated with the production and use of cryptoassets. The article highlights that these disclosures are crucial for fostering transparency and accountability in the crypto sector.

- The challenges that crypto firms may face in complying with MICA’s sustainability requirements, including the technical difficulty of measuring energy consumption accurately, the cost of compliance, and the need for standardised reporting methods. Zumo Tech emphasises that while these hurdles are significant, they are essential for the long-term viability of the industry.

- Zumo Tech outlines the broader implications of MICA on the crypto industry. The regulation is expected to drive innovation towards more energy-efficient technologies and practices. It could also influence investor behaviour, as greater transparency may attract environmentally conscious investors. The article suggests that, in the long run, these changes could lead to a more sustainable and resilient crypto ecosystem.

The guide written by Zumo provides a comprehensive overview of MICA’s sustainability disclosure requirements and their potential impact on the crypto industry. The regulation will enhance transparency and drive sustainability, but it presents significant compliance challenges.

To read the full guide, click the link here.

Preparing for DORA: What UK Fintechs Need to Know

Season 5, episode 5

Listen to the full episode here.

Set to reshape how financial entities across Europe and beyond approach digital resilience, DORA is more than just another compliance requirement, it’s a game-changer for fintechs, financial institutions, and third-party service providers.

What does this mean for UK fintechs, particularly in a post Brexit landscape? How can firms prepare, adapt, and turn compliance into a competitive advantage?

In this podcast we break down everything UK fintechs need to know about DORA, from key requirements to practical implementation strategies.

Participant-Rob Mossop – Chief Digital Officer (CDO) at Sword Group

-Luke Scanlon – Head of Fintech Propositions, Legal Director, Pinsent Masons

-Mick O’Connor – Founder and CEO at Haelo

Discover Agentic Workflows, the fintech revolutionising productivity with AI

6 months’ worth of work, completed in under 5 minutes, for less than 1 pence.

It’s a bold claim from Glasgow-based startup Agentic Workflows, and it’s turning heads in the AI space. By taking a highly innovative approach to Generative AI, they’ve built a platform that replaces cumbersome business processes with AI-powered “Agentic Workflows,” dramatically cutting costs, streamlining operations, and enhancing agility.

Rob Spencer, Founder and CTO, has been at the forefront of cutting-edge technology for most of his adult life. He started his career maintaining and calibrating weapon systems on the front line, later moving into IT, initially teaching Computer Science and practical IT at the Royal School of Signals. Following that, he transitioned into Financial Services in the City of London, where he led complex technical rollouts and transformational change initiatives.

It is that transformational change experience which provides the bedrock for Agentic Workflows. Imagine your company completing six months of work in under five minutes, at a fraction of the cost—how would that revolutionise your organisation’s productivity, customer service, and competitive edge?

Now, as a proud new member of the Fintech Scotland community, Agentic Workflows is eager to engage with fellow innovators, scale-ups, and established enterprises alike. Fintech firms often grapple with regulatory compliance, KYC processes, fraud detection, and operational inefficiencies, areas where AI-driven workflows could deliver immense value. By automating repetitive tasks and leveraging advanced data analytics, businesses can enhance their operational resilience, reduce costs, and streamline onboarding or transactional processes.

Moreover, generative AI has the potential to transform how customer interactions are handled, delivering hyper-personalised financial solutions and insights. Agentic Workflows’ platform aims to bridge the gap between technology potential and real-world application, helping firms quickly deploy AI solutions without the typical complexities and overheads of large-scale software projects. As the fintech ecosystem continues to evolve, partnering with an agile AI platform can be a powerful way to stay ahead in a competitive market.

With the technology developed and the platform built, Agentic Workflows is now looking to understand the challenges you face. If you’re exploring ways to harness the transformative power of AI within your organisation, or if you simply want to discover the art of the possible, please get in touch via the Agentic Workflows website. We look forward to collaborating with you and helping shape the future of financial services in Scotland and beyond.

The European Sustainability Reporting Standards and Opportunities for Financial Services

This white paper introduces the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), which underpin the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD); a core component of the EU’s Sustainable Finance Framework. It introduces the key concepts of the standards, and breaks down the disclosure requirements of cross-cutting and topical standards, such as biodiversity and ecosystems so that:

1. Corporations have a better understanding of what they must produce to adhere to the standards; and

2. Financial Services have a better understanding of what metrics they will have available to them to better assess risk, develop new financial products and ease their own disclosure requirement burden, through a direct mapping of the ESRS-SFDR only datapoints provided in Annex A.

3. Prepares the reader for the data mapping of White Paper 3: Mapping ESRS Disclosure Datapoints to Relevant Datasets in the series, where specific topics and datapoints are mapped directly to relevant datasets that can be used as part of their analysis.

A key learning is that the ESRS disclosures will be provided in digitally tagged format, eXtensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL), simplifying reporting and presenting new opportunities across the Financial Services sector, such as enhanced investment analysis, including aggregation of sector/country level data and automated analysis, or integration into traditional analysis workflows.