ESG Greenwashing And Applications of AI For Measurement

“ESG greenwashing” refers to the strategic communication tactics firms use to

selectively disclose their ESG conduct to stakeholders.

ESG greenwashing strategy, while it may attract and satisfy stakeholders at the beginning, may cause different issues for firms later, such as adverse publicity, lobbying, or boycott campaigns by consumer or pressure groups or divestment by socially responsible investors. The complex impacts of ESG

greenwashing underscore the imperative of discerning and quantifying instances of such practices. We aim to consolidate recent literature reviews of ESG greenwashing, methodologies to measure ESG greenwashing and developing applications of AI, text analysis and machine learning models to advance such measurement.

This white paper makes significant contributions to policy developments, such as the greenwashing regulations of the UK FCA and the European Parliament.

Simplifying Compliance through Explainable Intelligent Automation

We discuss how explainability in AI-systems can deliver transparency and build trust

towards greater adoption of automation to support financial regulation compliance among

banks and financial services firms.

We uniquely propose the concept of Explainable Intelligent Automation as the next generation of Intelligent Automation. Explainable Intelligent Automation seeks to leverage emerging innovations in the area of Explainable Artificial Intelligence. AI systems underlying Intelligent Automation bring considerable advantages to the task of automating compliance processes. A barrier to AI adoption though is the black-box nature of the machine learning techniques delivering the outcomes, which is exacerbated by the pursuit of increasingly complex frameworks, such as deep learning, in the delivery of performance accuracy.

Through articulating the business value of Robotic Process Automation

and Intelligent Automation, we consider the potential for Explainable Intelligent Automation

to add value. The solution framework sets out the Explainable Intelligent Automation

framework, as the interface of Robotic Process Automation, Business Process Management

and Explainable Artificial Intelligence. We discuss key considerations of an organisation in

terms of setting strategic priorities around the explainability of AI systems, the technical

considerations in Explainable Artificial Intelligence analytics, and the imperative to evaluate

explanations.

Explainable AI For Financial Risk Management

We overview the opportunities that Explainable AI (XAI) offer to enhance financial risk

management practice, which feeds into the objective of simplifying compliance for banking and

financial services organisations. We provide a clear problem statement, which makes the case for

explainability around AI systems from the business and the regulatory perspective.

A comprehensive literature review positions the study and informs the solution framework proposed. The solution framework sets out the key considerations of an organisation in terms of setting strategic priorities around the explainability of AI systems, the institution of appropriate model governance structures, the technical considerations in XAI analytics, and the imperative to evaluate explanations.

The use case demonstration brings the XAI discussion to life through an application to AI based credit risk management, with focus on credit default prediction.

Financial Regulation Innovation Lab – Exploring the intersection of quantum computing and the finance sector

As part of the 4th FRIL theme focusing on innovation to address financial crime, the FRIL team along with Alliance for Research Challenge in Quantum Technologies (Quantum ARC) and Technology Scotland hosted a roundtable to explore and catalyse the opportunities present now and in the near-future between quantum computing and the finance sector.

The discussion spanned a broad range of topics at the intersection of quantum and finance, with various opportunities and risks highlighted. Within these opportunities and risks, the discussion emphasised the critical need in thinking in relation to economic crime and fraud, which we look forward to progressing through the 4th FRIL programme currently live focusing on ‘innovation to address financial crime’.

What is Quantum Technology and the risks it presents?

McKinsey states quantum technology could create value worth trillions of dollars within the next decade with the finance sector identified as a sector that could see the earliest impact, however the concept remains relatively unknown to most. The term quantum technology broadly relates to science that applies quantum mechanics to a given field of technology, and refers to a subset of fields such as quantum computing, quantum sensing, quantum imaging, or quantum communications.

For the purposes of this blog, we will be focusing on quantum computing, which utilises qubits, concisely summarised by the World Economic Forum as –

Quibits are the equivalent of a classical bit, and the most fundamental unit for encoding information. Where a bit can be in a state of either on or off (0 or 1), a qubit can be in either 0 or 1 – or a combination of both. This is because of a superposition effect in quantum theory, which means that particles can exist simultaneously in multiple states.

In practice, this means not only can quantum computing provide a significant performance boost in processing, but it also has the potential to solve complex problems much faster than even the most powerful supercomputers today.

Whilst this kind of revolutionary power could deliver numerous opportunities for the finance sector, the risk rapidly materialises when considering public-key cryptography (PKC), which the security of nearly all Internet communications today is based on. The underpinning security of PKC relies on the difficulty of the mathematical problems and the challenge in which classical computers have in solving them. However, solving these mathematical problems with a general purpose quantum computer is considered easy, with Shor’s algorithm demonstrating this capability back in 1994, the challenge being that the power capabilities of a quantum computer to run the algorithm do not yet exist.

As highlighted by the NCSC, although advances in quantum computing technology continue to be made, quantum computers today are still limited, and suffer from relatively high error rates in each operation they perform. For organisations, however, this risk remains a priority for the thinking of today as bad actors are adopting a ‘harvest now, decrypt later’ approach to collect valuable, sensitive data in anticipation of power capabilities being on the horizon.

What is the current regulatory landscape at the intersection of quantum computing and the finance sector?

Regulatory agencies worldwide are battling with the balance between technology readiness levels and appropriate regulation or standard setting in relation to developments.

In October 2024, the UK Govt agreed with recommendations made by the Regulatory Horizons Committee (RHC – commissioned by DSIT to review the future needs of quantum technologies regulation to support innovation and growth) ‘that it is too early to establish regulatory requirements and legislation for quantum technologies at this stage given the nascency of the sector, but sustained action is required now to increase regulatory capability and enable a sector- and application-specific approach to regulating quantum technologies in the future’. When considering the finance sector specifically, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority has demonstrated its position as a leading voice in the quantum security domain through collaborative initiatives with the World Economic Forum, where research was published offering guidance for businesses and regulators to ensure a collaborative and globally harmonised approach to quantum security.

Looking further afield at the international landscape, momentum continues to evolve at pace, and earlier this year we also saw the US agency National Institute of Standards & Technology (NIST) finalised several post quantum encryption standards. With these standards, NIST encouraged large organisations, including those across the finance sector, to begin transitioning to the new standards as soon as possible. Regulatory authorities in Singapore have also recently launched a ‘Quantum Track’ within their Financial Sector Technology & Innovation Scheme (FSTI 3.0), with an additional S$100 million earmarked to support innovation in quantum and AI.

Despite this progress, participants in the discussion broadly agreed there is still a long way to go when assessing the regulatory and standard setting landscape of quantum.

How can we collectively progress successful collaboration around the exploration of quantum technologies?

The consensus of the discussion emphasised that the fundamental principles for continued collaboration span across the triple helix of engagement from industry, academia and regulatory colleagues, mirroring the principles that underpin the Financial Regulation Innovation Lab. Here at FRIL we will continue to actively convene stakeholders across these groups on topics that present both opportunities and risks in financial regulation, exploring how innovative propositions and ways of working can be progressed across the ecosystem.

Across the FinTech Scotland cluster there are various collaborative projects exploring the beneficial and responsible exploration of quantum technologies. One of which, highlighted by roundtable attendees, is the BT Quantum Key Distribution project. The NCSC outlines that Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) mitigates the quantum threat to key agreement using properties of quantum mechanics, rather than hard mathematical problems, to provide security. We look forward to continuing to engage with our partners in the BT team on their learnings throughout this programme and sharing insights across the cluster.

Challenges were highlighted around accessing and sharing data, which continues to be a barrier for innovators and researchers in this area. Discussion touched on the potential of synthetic data in aiding progress for development activities, and reference to the success of regulatory initiatives such as the FCA Digital Sandbox in already going some of the way to knock down these barriers. Risks were also highlighted around the danger that advancements in quantum could be dominated by existing major players in the market, further emphasising the importance of initiatives that support democratising the playing field for innovators in this space to enable competition and avoid monopolisation.

What’s next in the intersection of quantum and finance?

Reflections were made on the rapid evolution of AI, and the opportunities to respond differently as we look forward to the evolving risks and opportunities that quantum presents. These lessons range from the debate around explainability, and the potential opportunities quantum presents in this field, through to the pace at which regulation and standard setting is struggling to keep up with the technology.

There was a broad agreement across attendees that priority use cases for the finance sector in regards to quantum computing need refinement, with possibilities spanning from the use of quantum technologies by bad actors through to organisational adoption of quantum technologies. Attendees also highlighted the opportunities that can be explored with quantum technology as we look to areas such as open finance and the value that can be derived from this data to create beneficial and responsible innovation.

The FRIL Innovation to Address Financial Crime programme lays the foundations to begin testing some of this thinking, as evidenced through the roundtable and also the broader innovation call series, and we will continue to engage with experts across the ecosystem in the long term roadmap of FRIL focus areas. We are looking forward to engaging with innovators across the industry led use cases in this programme, exploring where potential quantum computing advancements may provide opportunities to more effectively tackle financial crime risks.

Interested in exploring more? The key contacts across the Financial Regulation Innovation Lab on this topic are:

- Lauren Cassells, Research and Innovation Programme Manager (lauren.cassells@fintechscotland.com)

- Gemma Milne, Research Associate, University of Glasgow (gemma.milne@glasgow.ac.uk)

Open Finance and Carbon Neutral Banking

Recent industry insights show that banks still face significant constraints in measuring indirect Green House Gas (GHG) emissions owing to data limitations and a lack of harmonised methodologies.

At the same time, banks and other financial institutions hold large volumes of consumer data that can be leveraged to estimate GHG emissions albeit financial transaction data are privately owned with restricted access. This paper discusses how an open finance framework can be used to aggregate consumer transaction data across multiple financial products to compute carbon footprints.

It highlights a step-by-step approach to carbon footprint estimation and discusses the consideration for using microdata for emission computation.

Regulatory Innovations and Anti-Greenwashing: UK/EU Strategic Insights

Financial Regulation Innovation Lab – University of Strathclyde

Given the growing global concern for sustainability and environmental responsibility, the practice of greenwashing has emerged as a critical challenge. Greenwashing occurs when companies exaggerate or falsely represent their environmental efforts to stakeholders, creating a misleading image of sustainability that masks their true impact. The United Nations (UN) highlights the severity of this issue, defining greenwashing as the behaviour of “misleading the public to believe that a company or other entity is doing more to protect the environment than it is”[1]. This deceptive practice can present significant challenges in addressing climate change, undermine consumer trust, and disrupt the market.

In response to this issue, the UK and EU have implemented a series of rules and regulations guiding firms toward anti-greenwashing practices. The EU, for instance, formally endorsed the Greenwashing Directive on 17 Jan 2024, which requires companies to substantiate their environmental claims with clear, reliable evidence. The UK has also established guidelines to combat greenwashing, with oversight from the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). Additionally, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has introduced a new anti-greenwashing rule, effective since 31 May 2024, further strengthening the regulatory framework to ensure the integrity of environmental claims made by firms.

In this blog, we cover the latest anti-greenwashing regulations in the UK and EU, examining their strategic insights in respect of promoting transparency and authenticity in sustainable practices. We discuss the consistency of these regulations, while also highlighting key differences in their approaches. Finally, we suggest potential future developments in these regulatory frameworks.

UK Regulations Targeting Greenwashing Practices

Prior to 2021 in the UK, consumer protection and advertising regulations had been in place to address potentially misleading sustainability claims. However, these regulations lack a structured and enforceable framework specifically designed to address and mitigate such issues comprehensively. After 2021, the CMA launched a review over the potential misleading sustainability claims regarding the eco-friendliness of clothing lines in the fashion sector, including brands such as ASOS, Boohoo and George at Asda (Competition and Markets Authority, 2023[2]). Additionally, to help companies understand how to communicate their green credentials while reducing the risk of misleading shoppers, the CMA has published the Green Claims Code[3], focusing on six principles based on existing consumer laws. The Green Claims Code regulates companies that they “must not omit or hide important information” and “must consider the full life cycle of the product” when making green claims. For example, a loaf of bread labelled as “Organic Sourdough” would be misleading if it does not meet the sector-specific requirement that food products must contain at least 95% organic ingredients to be labelled as organic. The CMA is able to fine companies up to £300,000, or 10% of a company’ annual turnover (whichever is higher), for breaching consumer laws, and up to 5% of a company’s annual global turnover, with an additional daily penalty of 5% of daily turnover during non-compliance, for failing to comply with a direction (Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, 2022[4]).

However, recent incidents have revealed that greenwashing practices have increasingly surfaced in the banking sector. Therefore, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)’s Anti-greenwashing Rule (AGR/The Rule) came into force in May 31, 2024, with the aim of protecting investors against firms’ greenwashing intentions. The Rule is stated under Section ESG 4.3.1R of the FCA’s Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Sourcebook, published through their Policy Statement on Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR) and investment labels (the Policy Statement). The Rule requires all FCA-authorised firms providing sustainability-related financial products/services and/or financial promotions to clients in the UK to deliver claims that are ‘fair, clear and not misleading’, and are consistent with their sustainability characteristics. Specifically, AGR Guidance underpins the following principles (referred to as the ‘4 Cs’):

- Correct and capable of being substantiated – claims should be factually correct and not provide conflicting or contradictory information; the firm’s products/services should live up to the claims made with robust and credible supporting evidence; the firm should regularly review and maintain their claims and evidence following AGR on an ongoing basis; the firm should make the evidence publicly available in an easily accessible way.

- Clear and presented in a way that can be understood – claims should be made transparent, straightforward, useful, and generally understood by all intended audiences; firms should maintain the overall impression and visual presentation to be consistent with their claims; firms subject to Consumer Duty should test their communications where appropriate and ensure they have the necessary information to understand and monitor customer outcomes.

- Complete – claims should not omit or hide important information and should consider the full lifecycle of the products/services that might influence decision-making. This extends to not highlighting only positive sustainability impacts where this disguises negative impacts.

- Comparisons should be fair and meaningful – comparisons mentioning other products/services should be made in a fair and meaningful manner, whether in relation to a previous version of the same product or service or to a competitor’s product or service. This should enable the audience to make informed decisions about the products/services.

EU Regulations Targeting Greenwashing Practices

In the EU, the battle against greenwashing is also intensive. In 2020, the European Commission found that 53% of examined environmental claims in the EU were vague, misleading or unfounded, and 40% were unsubstantiated (European Commission, 2023[5]). The Consumer Protection Cooperation (CPC), a network under authority of the Consumer Protection Cooperation Regulation and with the coordination of the European Commission, takes action to address cross-border violation of consumer protection at EU level. BEUC can post alerts about emerging market threats associated with greenwashing and their information is then directly accessible by enforcement authorities[6].

In January 2024, the European Parliament formally approved its Greenwashing Directive[7], requiring member states to introduce stricter rules surrounding the use of environmental claims by companies. The regulation complements and further operationalises the proposal for a Directive on empowering consumers in the green transition in 2022. In Parliament, the file has been allocated jointly to the Committees on Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO) and on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI).

The Greenwashing Directive covers all sustainability claims that relate to a product, a brand, a company, or a service made in a business-to-consumer (“B2C”) context. Under the Directive, sustainability claims cover both environmental or “green” claims and so-called “social characteristic” claims. Only sustainability labels based on official certification schemes or established by public authorities will be permitted in the EU. In addition to “greenwashing”, bluewashing[8]issues also fall within the scope of the Greenwashing Directive. The Greenwashing Directive also introduces a clear definition of “environmental and social characteristics with specific examples; specifically, matters relating to animal welfare or vegan are also considered as social characteristic claims”.

Currently, the EU has been taking stronger actions against greenwashing. The European Parliament and Council have reached a provisional agreement on new rules to ban misleading advertisements and provide consumers with better product information; for instance, generic environmental claims, e.g. “environmentally friendly”, “natural”, “biodegradable”, “climate neutral” or “eco”, without proof of recognised excellent environmental performance relevant to the claim. False or unfounded product durability claims that promote replacement or repairability earlier than necessary will also be banned. Once the Greenwashing Directive is published in the Official Journal of the EU and enters into force, Member States will have 24 months to transpose the Directive into their national legislation. However, some Member States, such as France, Germany, and the Netherlands, are expected to implement these rules earlier, as their regulators, NGOs and consumer organisations and courts have already started to enforce against greenwashing.

A Comparative Perspective on UK/EU Anti-greenwashing Regulatory Frameworks

The overview of the UK’s and the EU’s anti-greenwashing regulatory frameworks reveals a consistent and unified effort to combat greenwashing, aiming to foster consumer trust and promote true sustainability in the market. These frameworks reflect a shared goal of combating greenwashing, with recent developments showing an increased focus on addressing specific challenges and complex cases associated with misleading environmental claims. Both regulatory frameworks emphasise the importance of accountability and verification, requiring companies to substantiate their environmental claims with credible evidence that can be verified by consumers. The regulations are frequently updated, underscoring the recognition by both the UK and the EU that greenwashing is a critical issue that must be tackled to ensure transparency and protect consumers.

It is also important to acknowledge some differences in the anti-greenwashing regulatory frameworks between the two regions. The UK advocates a principle-based regulatory approach that encourages companies to adhere to broad principles of fairness and honesty in their environmental claims. Over the period 2015 to 2022, the FCA has outlined various measures to address greenwashing, including requiring firms to withdraw or amend misleading advertisements, banning promotions, and issuing public alerts. This approach fosters flexibility, innovation, and dynamic solutions to sustainability challenges by allowing companies to tailor their environmental claims and practices following the rules. However, it has not publicly disclosed any specific sanctions against companies within the Advisors and Intermediaries portfolio for greenwashing (Financial Conduct Authority, 2022[9]). Compared to the UK, the EU employs a legislative-based framework characterised by stricter enforcement and detailed, uniform rules. Although it has not been officially implemented, the EU Parliament’s proposal clearly called out sanctions for businesses guilty of breaking the rules, including temporary exclusion from public tenders, loss of their revenues, and a fine of at least four per cent (4%) of their annual turnover. The most recent action by the EU after the introduction of new proposal was the case against greenwashing claims of the aviation industry. In May 2024, the EU Commission and EU consumer protection authorities contacted twenty (20) airlines regarding claims that “the CO2 emissions caused by a flight could be offset by climate projects or through the use of sustainable fuels, to which the consumers could contribute by paying additional fees”. The airlines were asked to respond within thirty (30) days with their proposed solutions to address the concerns. After that, authorities will discuss and monitor the implementation of agreed upon solutions, and if the required steps are not followed accordingly, further actions, including sanctions, could be taken[10]. This rigorous approach guarantees uniform standards and accountability throughout the EU, effectively managing the complexities of coordinating regulations across various legal systems and markets.

One other difference comes from the sectoral focus. The FCA, as an institution that serves to regulate financial services and markets in the UK, has recently directed its Anti-greenwashing Rule specifically towards greenwashing behaviors within financial services, financial institutions, and financial products. Besides this, the CMA’s Green Claims Code primarily targets the consumer goods sector, aiming to address misleading environmental claims across a wide range of consumer products. In contrast, the EU’s Greenwashing Directive takes a broader approach, applying to a wide range of sectors and industries across the European market.

Potential Future Developments in Anti-greenwashing Regulatory Frameworks

We acknowledge the critical advancements in recent anti-greenwashing regulatory frameworks within both the UK and the EU. We outline here several prospective developments that could be considered to enhance the effectiveness of combating greenwashing practices.

The regulatory framework should broaden its focus to encompass not only environmental practices but also social and governance aspects, as it evolves to address ESG-related greenwashing. For instance, the finalised Anti-greenwashing Rule from the FCA in the UK has received positive feedback overall from respondent companies, but some concerns have been pointed out regarding the clarity of sustainability’s taxonomy, which should go beyond environmental / climate-related claims to cover claims relating to “social issues”, and even corporate social responsibility initiatives. The terms “environmental/social characteristics” should be more clearly defined and elaborated from other terms used in the guidance, such as “complete”, “life cycle of the product”, “regular review” and “periodically monitor”. Moreover, there is less of a focus on claims regarding governance, despite the FCA stating clearly that: “We consider governance to be an enabler of environmental or social outcomes, rather than an end in itself, and we refer to ‘sustainability characteristics’ as ‘environmental or social characteristics” (Financial Conduct Authority, 2024[11]).

We also recommend that increased attention be directed towards small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). From perspective of stakeholders, SMEunited[12] is worried that, although the proposed Greenwashing Directive from the EU would exempt micro-enterprises from obligations ((Articles 3(3), 4(6), 5(7)), SMEs could be affected indirectly through market pressure or consumers who suspect they do not comply with the obligations. Improved support measures should be put in place therefore, in case micro-enterprises would like to apply the requirements of the directive voluntarily, through the introduction of a simplified EU-level tool and by facilitating lifecycle analysis for SMEs at EU level. IMA[13]-Europe suggests that the Commission should avoid ‘over-regulating’ and reduce unnecessary administrative burdens; for instance, procedures for firms to obtain more certificates of conformity for green-claim products should be simplified, and authorities should allocate sufficient time for firms to remedy for their violations before applying penalties.

Ngoc Anh Chu is a PhD candidate and a scholarship recipient from Department of Accounting & Finance, Strathclyde Business School (SBS). Her current work is related to artificial intelligence and machine learning, specifically in Natural Language Processing (NLP) and eXplainable AI (XAI) applications in the field of ESG and Sustainable Finance. She previously worked in Integrated International Tax Consulting Department at KPMG Vietnam and later obtained her MSc in Financial Technology from SBS in 2023 with distinction and academic award from the department. Her dedication in integrating advanced technologies to improve transparency and reliability of financial sector highlights her innovative approach and commitment to driving impactful research, contributing to sustainability, and developing solutions that foster a more accountable industry.

Email: ngoc.chu@strath.ac.uk

Daniel Dao is a Research Associate at the Financial Regulation Innovation Lab (FRIL), Department of Accounting and Finance, University of Strathclyde Business School; and a Research Economist (Consultant) at the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), The World Bank, Washington DC Headquarters. He is a CFA Charterholder and an active member of the CFA UK. He has earned PhD in Finance from Coventry University, UK; MBA in Finance from Bangor University, UK; and MSc in Financial Engineering from WorldQuant University, US. His expertise lies in the fields of Fintech; Sustainable Finance; Productivity, Innovation, & Growth; with proficiency extending to data science techniques and advanced analytics, with a specific focus on artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural language processing (NLP). He has published in internationally leading journals, including British Journal of Management (ABS-4), Information and Management (ABS-3*), and various policy and industry research reports affiliated with The World Bank (Dominican Economic Memorandum, 2023; World Development Report, 2024; Labour and Policy Reform, 2024) and Fintech Scotland (White papers and Blog Posts in AI, Fintech, ESG, and Financial Regulation)

Email: daniel.dao@strath.ac.uk

[1] The UN: Greenwashing – The deceptive tactics behind environmental claims: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/climate-issues/greenwashing#:~:text=By%20misleading%20the%20public%20to,delay%20concrete%20and%20credible%20action.

[2] Competition and Markets Authority – ASOS, Boohoo and Asda: greenwashing investigation: https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/asos-boohoo-and-asda-greenwashing-investigation

[3] Green Claims Code: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/green-claims-code-making-environmental-claims/green-claims-and-your-business

[4] Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy – Reforming competition and consumer policy:

[5] European Commission – Consumer protection: enabling sustainable choices and ending greenwashing: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_1692

[6] Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs, which is translated into “European Bureau of Consumers’ Unions”.

[7] Greenwashing Directive: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2023)753958

[8] Bluewashing refers to companies who signed the United Nations Global Compact and its principles but did not make any actual policy reforms. Bluewashing differs from greenwashing as it focuses more on social and economic responsibility rather than the environment (Forbes – Bluewashing joins greenwashing as the new corporate whitewashing: https://www.forbes.com/sites/timothyjmcclimon/2022/10/03/bluewashing-joins-greenwashing-as-the-new-corporate-whitewashing/)

[9] Financial Conduct Authority – Information on firms sanctioned for greenwashing – April 2022: https://www.fca.org.uk/freedom-information/information-firms-sanctioned-greenwashing-april-2022

[10] European Commission – Commission and national consumer protection authorities starts action against 20 airlines for misleading greenwashing practices: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_232256

[11] Financial Conduct Authority – Finalised Guidance: https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/finalised-guidance/fg24-3.pdf

[12] European Association of Craft, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

[13] Industrial Minerals Association

Transparency, explainability and fairness in approaches to AI regulation: Takeaways from the Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence

a Financial Regulation Innovation Lab, Strathclyde Business School, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, Scotland

b Michael Smurfit Graduate Business School, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Introduction and Purpose

AI offers amazing opportunities, but has the potential for both harm and good. Used responsibly it can perhaps redress urgent concerns. Conversely, careless use may worsen societal harms – fraud, discrimination, bias, and disinformation among others. AI deployment for good and towards achieving its many benefits necessitates mitigation of its considerable risks, demanding efforts from government, the private sector, academia, and civil society (Biden Jr., 2023).

Thus, on the 30th of October 2023 an Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) was issued from the White House’s Briefing Room under the authority of President Biden (Biden Jr., 2023). Through the order’s authority, the utmost priority was placed on AI development and use governance via a coordinated, Federal Government-wide approach. The pace of AI capability advancements compelled this action (Biden Jr., 2023).

The order’s impact is assured by the force of law, and federal/executive departments and agencies[1] were made accountable for several duties within it. The aim is to achieve a more innovative, secure, productive, and prosperous future for equitable AI governance (Biden Jr., 2023). Consequently, they have undertaken initiatives to assist in shaping AI policy and advance the safe and responsible development and utilization of AI.[2]

The US’s systematic importance in shaping the global economic landscape makes it interesting to explore its approach to AI regulation (Jain, 2024). Thus, aspects centred around transparency, fairness and explainability within the Executive Order are outlined and form the basis of this piece. A particular emphasis is placed on Sections 7 (Advancing Equity and Civil Rights) and Section 8 (Protecting Consumers, Patients, Passengers, and Students), given the relevance of their respective content to explainability, transparency, and fairness in the context of this article. Finally, a juxtaposition against EU and UK regulatory approaches is made to draw out similarities and differences.

Executive Order Structure

The executive order is structured into the following sections:

- Purpose.

- Policy and Principles.

- Definitions.

- Ensuring the Safety and Security of AI Technology.

- Promoting Innovation and Competition.

- Supporting Workers.

- Advancing Equity and Civil Rights.

- Protecting Consumers, Patients, Passengers, and Students.

- Protecting Privacy.

- Advancing Federal Government Use of AI.

- Strengthening American Leadership Abroad.

- Implementation.

- General Provisions.

Policy and principles

Eight guiding priorities and adhering principles are outlined for agencies, to comply with the order’s mandate, as appropriate and consistent with applicable law, while, where feasible, considering the views of other agencies, industry, academia, civil society, labor unions, international allies and partners, and other relevant organizations (Biden Jr., 2023). In synopsis, they are:[3]

(a) Safe and secure AI, requiring robust, reliable, repeatable, and standardized AI system evaluations, as well as policies, institutions, and other mechanisms to test, understand, and mitigate risks before use. This includes addressing the most pressing security risks of AI systems, while navigating AI’s opacity and complexity (Biden Jr., 2023).

(b) Promote responsible innovation, competition, and collaboration for AI leadership, and unlock potential for society’s most difficult challenges, through related education, training, development, research, and capacity investments. Concurrently, tackle novel intellectual property (IP) questions and other problems to shield inventors and creators (Biden Jr., 2023).

(c) Responsible AI development and use requiring commitment to supporting workers. As new jobs and industries are created, workers need a seat at the table, including collective bargaining, so they benefit from opportunities. Job training and education to be adapted for a diverse workforce and providing access to AI-created opportunities (Biden Jr., 2023).

(d) AI policies consistent with the Administration’s dedication to advancing equity and civil rights. AI use to disadvantage those already too often denied equal opportunity and justice should not be tolerated. From hiring to housing to healthcare, AI use can deepen discrimination and bias, rather than improving quality of life (Biden Jr., 2023).

(e) Protect interest of those increasingly using, interacting with, or purchasing AI and enabled products in daily lives. New technology usage does not excuse organizations from legal obligations, and hard-won consumer protections are more important in moments of technological change (Biden Jr., 2023).

(f) Protect privacy and civil liberties as AI continues advancing. AI makes it easier to extract, re-identify, link, infer, and act on sensitive information about people’s identities, locations, habits, and desires. AI’s capabilities in these areas can increase the risk that personal data is exploited and exposed (Biden Jr., 2023).

(g) Manage the risks from Federal Government’s own AI use and increase its internal capacity to regulate, govern, and support responsible AI use for better results. Steps are to be taken to attract, retain, and develop public service-oriented AI professionals, including from underserved communities, across disciplines and ease AI professionals’ path into the Federal Government to help harness and govern AI (Biden Jr., 2023).

(h) Lead the way to global societal, economic, and technological progress, as in previous eras of disruptive innovation and change. This is not measured solely by technological advancements the country makes. Effective leadership also means pioneering systems and safeguards to deploy technology responsibly — and building and promoting safeguards with the rest of the world (Biden Jr., 2023).

Definitions

“Artificial intelligence” or “AI” is defined in the order as a machine-based system that can, for a given set of human-defined objectives, make predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing real or virtual environments. Artificial intelligence systems use machine- and human-based inputs to perceive real and virtual environments; abstract such perceptions into models through analysis in an automated manner; and use model inference to formulate options for information or action (Biden Jr., 2023).

Further, “AI model” in the order means a component of an information system that implements AI technology and uses computational, statistical, or machine-learning techniques to produce outputs from a given set of inputs (Biden Jr., 2023).

Finally, the order’s “AI system” definition is any data system, software, hardware, application, tool, or utility that operates in whole or in part using AI (Biden Jr., 2023).

Transparency, explainability and fairness

While some notable elements of transparency, explainability and fairness are present, directly or indirectly, in other sections of the order, given their emphasised pertinence for human, consumer, and fundamental rights implications (Jain, 2024), over and above the guiding principles and policies discussed earlier, Section 7 and Section 8 delve into the greatest detail on these areas of particular interest.

Section 7 Advancing Equity and Civil Rights provides edification and guidance predominantly in relation to bias and discrimination from an AI perspective. This is in the context of varied rights including those related to the dispensation of criminal justice, and government benefits and programs. Finally, this is also done in the context of the broader economy: specifically, in so far as AI decision making is concerned, whether for disabilities, hiring, housing, consumer financial markets, tenant screening, among others (Biden Jr., 2023).[4]

Section 8 Protecting Consumers, Patients, Passengers, and Students illustrates, from the lens of AI, the direction and principles in relation to aspects of healthcare, public health, and human services. It also clarifies in relation to facets of bias and discrimination in such contexts. Moreover, it details guidance on transportation, education, and communication insofar as AI is concerned (Biden Jr., 2023).[5]

Disparities and parities viz-a-viz the UK and EU

Unlike the UK, and like the EU, explicit definitions for AI are mapped out within the order as highlighted earlier (Jain, 2024). For the most part, the order is phrased in the context of the US and its applicability is for the most part confined to the US, but similar to both the UK and EU, instances exist where international applicability comes into play (Jain, 2024). Notably however, the onus is largely laid upon existing regulatory bodies for the implementation of the order like the UK, albeit with the distinction that some existing US bodies (for example, TechCongress) mostly, if not entirely, have AI within their remits. Thus, in the latter respect, approach of the US is more similar to that of the EU, and perhaps most accurately defined as a combination of the two (Jain, 2024).

In so far as fairness, explainability and transparency are concerned, there is a very holistic emphasis from US lawmakers along several unique considerations. In this, the approach is more akin to that of the EU. As far as caveats and advantages are concerned, a comparison between the US and the UK can be drawn that is broadly parallel to the contrast between the EU and the UK. Specifically, due to its stricter approach, and bureaucratic structure, it will necessitate expending significantly more compliance time, cost, and effort. However, such regulatory guidelines have stronger ethical grounding, possibly ensuring the best interests of relevant stakeholders, and avoiding dark innovation, bad players, reputational damage, and insidious misuse (Jain, 2024). Lastly as seen for the EU and UK (Jain, 2024), fairness, explainability, and transparency once again come to the fore as key considerations in regulating AI within the order. They are also ubiquitously present principles in the approach of the US as evidenced above, underlining their importance and salience in lawmakers’ minds.

Future topics

Expounding upon and assessing the evolution of this regulatory space may be compelling subjects for future articles, as they could hold manifold implications for explainability, transparency and fairness. Further iterations or final versions of specific draft guidance (referenced in footnotes earlier in this piece) created in response to this order could be analysed in further detail (for instance, see here), and comparisons with other similar frameworks (for instance, see here) may be of interest.

References

Biden Jr., J. R. (2023, October 30). Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved from The White House’s Official Website – Briefing Room – Presidential Actions: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/10/30/executive-order-on-the-safe-secure-and-trustworthy-development-and-use-of-artificial-intelligence/

Jain, K. (2024, April 03). How transparency, explainability and fairness are being connected under UK and EU approaches to AI regulation. Retrieved from FinTech Scotland: https://eur02.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fintechscotland.com%2Fhow-transparency-explainability-and-fairness-are-being-connected-under-uk-and-eu-approaches-to-ai-regulation%2F&data=05%7C02%7Ckushagra.jain%40strath.ac.uk%7C1f806I

Image created by OpenAI’s DALL·E, based on an article summary provided by ChatGPT.

Short courses, microcredentials and skills development

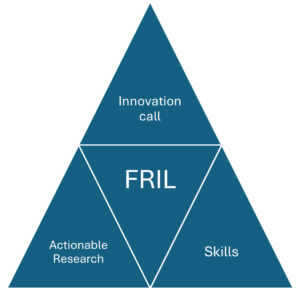

Financial Regulation Innovation Lab (FRIL) is a UKRI funded industry-led innovation programme that aims to address challenges and facilitate innovations in the landscape of financial regulation. FRIL comprises four pillars: innovation calls, actionable research, knowledge exchange and skills development, with each pillar informing and reinforcing each other. As part of the FRIL Team, our Skills Development Team have been focusing on developing short courses and microcredentials to support professionals in the financial sector for upskilling and reskilling. This blog focuses on the skills development aspect of FRIL.

1. Why skills development is important in FRIL?

Skills development offers clear benefits to individuals and organisations (FSSC, 2022).

For individuals, skills development enables them to update skills and knowledge, acquire new skills and capabilities, work more effectively, enhance performance, which makes them become more valuable to their current and future employers. This then translates to better career prospects.

For organisations, investing in skills development of their workforce can help increase productivity, drive innovation, enhance employee engagement, teamworking and reduce employee turnover. Engaged employees are more likely to be proactive, creative, work well with others, and be committed to achieving positive customer outcomes.

Skills development also offers benefits to policy makers. Upskilling and reskilling the workforce is key to enable a prosperous, resilient and sustainable economy. Promoting, encouraging and supporting skills development can help align with the strategic objectives of policy makers and ultimately achieve the wider social and economic benefits (Weston, 2024). For example, the Scottish Government has set an ambitious target for net zero greenhouse emission by 2045 and 75% production by 2030 (Rubio et al, 2022). This requires the workforce across industries to be timely and adequately provided with relevant green skills development training.

2. What are the external factors that drive the necessity of skills development?

2.1 Technological development

Fast changing technological development driven by industrial revolution 4.0, has changed the nature of work, where we work, how we work and what we are working on. According to OECD (2019), about 14% of jobs could be replaced and 32% transformed in the next 20 years. New jobs will be created and others becoming obsolete. The skills and knowledge needed to meet the demands of the evolving job market will continue to change, rapidly, creating skill gaps across the global economy (Stalidis & Kyriazidou, 2024). Skill development is key to adapt to this rapid change, creating both personal and organisational competitive advantage and sustainable growth.

2.2 Net zero transition:

As we are moving towards the net zero transition, new skills focused on green practices become critical. However, the demand for green knowledge and skills seems to have outpaced the supply of graduates with sustainability skills. According to PwC (2023), the number of vacancies of green jobs in the financial sector increased by three folds, from about 500 to nearly 17,000 within three years; in contrast, only 900 of them are likely to be filled by graduates trained with sustainability skills. Simply relying on graduates to fulfil the vacancies is not sufficient. Therefore, upskilling and reskilling the existing workforce in the sector through skills development programmes becomes key to address this emerging industry skill gap and where supported in public policy can address broader societal concerns with a just transition to climate change and fair work .

2.3 Changing demographics

People live longer, and they work longer (Loretto, 2016). The knowledge and skills that were acquired when they graduated will no longer sustain for the rest of their working life. They need to continue to upskill and reskill to stay competitive and meet the changing demand of the job market. Lifelong learning and skills development is important to all stakeholders in the financial services ecosystem, including the government, employers, educators and individuals.

2.4 Other drivers

Other external drivers include changing customer behaviours, products and services, as well as policies and regulations. They are particularly important to the financial sector.

3. FRIL approach to skills development

As a key pillar in FRIL, our skills development team works to address industry skill gaps, offer just-in-time and on-demand skills development courses, upskill and reskill the workforce and support the financial regulation innovation.

It is important to remember that the financial services industry is in a unique position right now, as on one hand, they need their employees to have the knowledge, skills and capabilities to follow guidelines and comply with regulations, on the other hand, they must innovate new products and services to attract new customers.

In this context, we adopted five principles to guide our skills development work. First, demand led. All our skills offerings are led by demand in the industry. These demands need to be endorsed by industry representatives. We have an Industry Steering Group and Skills Sub-group in the FRIL governance. They give feedback to our proposed skills courses both in terms of the target audience and the direction of the course. This helps us greatly in terms of making sure that the courses we are developing are addressing industry’s real demand.

Second, evidence based. We collate evidence from a variety of sources and triangulate them to validate our proposal on developing a specific course. These sources include industry reports, skills reports, contacts of FRIL’s strategic partners and the Fintech community. We are focusing on the future skills that are not only new themselves, but also the demand for which is growing rapidly.

Third, partnership enabled. Our skills team at the Adam Smith Business School work closely with Fintech Scotland and Strathclyde Business School colleagues on developing just in-time and in-demand skills programmes. We identify opportunities and feed them into each other to ensure a coherent development of short courses under FRIL.

Fourth, industry facilitated. We work closely with key members in the industry and involve them in the course development phase. These members offer us use cases, guest lectures and best practices to help us enrich our course offerings.

Figure 1. Alignment between three FRIL key pillars.

Last but not the least, the focus of our skills stream is aligned with the innovation call and actionable research. Insights and findings from the innovation call and actionable research can feed into the skills stream, and our skills development programme can also help address the challenges identified from the innovation call and actionable research.

4. Areas of focus

With the many skills in demand in the financial sector, our skills team focuses our resources and efforts and prioritises on those that are closely aligned with the FRIL innovation calls and actionable research topics. They are:

4.1 AI and compliance

Simplifying compliance through AI and emerging technologies

4.2 ESG

Supporting industry to promote and embed responsible and sustainable financial practices

4.3 Consumer duty

Supporting widening access and inclusion to those who do not currently engage or have limited engagement with financial support and information

4.4 Addressing financial crime

Supporting industry and citizens to detect and protect themselves from fraudulent actors and activities.

5. What do our skills development programmes include?

5.1 Short courses

These courses are focused and short, and usually requires 4-6 weeks’ learning.

5.2 Microcredentials

Microcredential are short courses that are credit bearing and offered by qualification awarding institutions. Microcredentials offer professionals the opportunity to claim for academic credits at the postgraduate level and stack the learning towards a higher qualification, i.e. Postgraduate Certificate. Microcredential is one of the key alternative credentials in the UK and EU learning markets and has been gaining tractions since the pandemic. They offer an effective way to upskill and reskill the workforce.

We understand not everyone has the time to undertake skills related course. In recognition of this, our skills team publish blogs and organise events to offer professionals informal learning. And finally, we also work as a catalyst and engage with the industry members to support their talent pipeline recruitment.

6. What short courses are currently on offer from the FRIL’s skill team?

6.1 AI & RegTech

Led by the University of Glasgow FRIL Skills Team, this course offers an in-depth introduction to the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in financial regulatory compliance within the evolving landscape of RegTech. Designed for financial professionals, compliance officers, and decision-makers, this course aims to deepen the understanding of AI, RegTech, and their integration into corporate compliance strategies and operations. It covers key concepts, challenges, opportunities, and innovations associated with AI adoption within the RegTech space.

Delivered on campus over six weeks, this course provides professional learners ample opportunities to interact and learn from the lecturers and peers.

7. What microcredentials are currently on offer from the FRIL skills team?

7.1 ESG Leadership

Led by the University of Glasgow FRIL Skills Team, this course takes a practical-application approach to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) integration into organizational practice. It introduces regulatory compliance, supply chain auditing, ESG data and analytics, and leadership and innovation practices as they relate to financial services, FinTech firms, and the relevant business ecosystem. Designed for professionals who want to move into sustainability roles, work in financial institutions as functional managers and those in fintech firms, this course combines regulatory and compliance questions with strategic development and leadership.

This microcredential is delivered over 6 weeks, fully online with a face-to-face capstone to consolidate learning.

8. AI Literacy

Led by the University of Strathclyde FRIL Skills Team, a suite of five micro credentials is currently under development: AI Curious – AI Explorer – AI Enthusiast – AI Expert as well as a stand-alone module, AI for Executives, with each microcredential focusing on a particular depth of understanding of AI. Delivery will be blended with a capstone in person session to consolidate learning and will have a with a regulatory risk and compliance focus.

9. Call to action:

Hope this blog offers you a clear overview of the progress our skills team has made at FRIL and the key skills development programmes currently on offer. The courses mentioned above are all to be delivered in the autumn of 2024, and we are calling for expression of interest. We have limited funded spaces so please register your interest as soon as possible with Xiang.Li@glasgow.ac.uk (for courses: AI and RegTech, ESG Leadership) and christine.sinclair@strath.ac.uk (for courses: AI Literacy at different levels). If you would like to collaborate with our skills team, please contact us.

References:

FSSC (2022). Mind the Gaps – Skills for the Future of Financial Services 2022. [online] Financial Services Skills. London, UK: Financial Services Skills Commission. Available from: https://financialservicesskills.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/FSSC-Future-Skills-Interactive-V13.pdf

Government Office for Science. (2017). Skills and lifelong learning: the benefits of adult learning. [Online]. [Accessed 23 June 2024]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/skills-and-lifelong-learning-the-benefits-of-adult-learning

Loretto, W. (2016). Extended Working Lives: What Do Older Employees Want?. In: Manfredi, S., Vickers, L. (eds) Challenges of Active Ageing. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-53251-0_9

OECD. (2019). OECD employment outlook 2019: the future of work. [Online]. [Accessed 20 June 2024]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9ee00155-en/1/2/2/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/9ee00155-en&_csp_=b4640e1ebac05eb1ce93dde646204a88&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=book#:~:text=2.2.-,3.,be%20affected%20by%20deep%20changes

PwC. (2023). An emerging green skills gap in the Financial Service sector risks Net Zero goals. [Online]. [Accessed 22 July 2024]. Available from: https://www.pwc.co.uk/press-room/press-releases/emerging-green-skills-gap-in-the-financial-service-sector.html

Rubio, J.C., Warhurst, C., and Anderson, P. (2022). [Online]. [Accessed 29 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.skillsdevelopmentscotland.co.uk/media/q2lhg1v5/green-jobs-in-scotland-report_final-4.pdf?_gl=1*fts9c2*_up*MQ..*_ga*NzE4MjE0NjUuMTcyNTA0MDcwMw..*_ga_2CRJE0HKFQ*MTcyNTA1MDcyMy4yLjAuMTcyNTA1MDcyMy4wLjAuMA..

Stalidis, G., Kyriazidou, S. (2024). Job Role Description and Skill Matching in a Rapidly Changing Labor Market Using Knowledge Engineering. In: Kavoura, A., Borges-Tiago, T., Tiago, F. (eds) Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism. ICSIMAT 2023. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-51038-0_21

Weston, T., (2024). Importance of skills: Economic and social benefits. [Online]. [Accessed 30 August 2024]. Available from: https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/the-importance-of-skills-economic-and-social-benefits/#:~:text=As%20well%20as%20helping%20businesses,knowledge%20and%20skills%20of%20populations”.

About the author

Dr Xiang Li work at the University of Glasgow Adam Smith Business School and contributes as researcher to the Financial Regulation Innovation Lab (a partnership funded by Innovate UK between FinTech Scotland, University of Strathclyde, and University of Glasgow).

Disclosures

I acknowledge funding from Innovate UK, award 10055559, Financial Regulation Innovation Lab.

Open Access. Some rights reserved.

Open Access. Some rights reserved. The publishers, the University of Glasgow and FinTech Scotland, and the author, Xiang Li, want to encourage the circulation of our work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. We therefore have an open access policy which enables anyone to access our content online without charge. Anyone can download, save, perform or distribute this work in any format, including translation, without written permission. This is subject to the terms of the Creative Commons By Share Alike licence. The main conditions are:

• The University of Glasgow, FinTech Scotland, and the authors are credited, including our web addresses www.gla.ac.uk, and www.fintechscotland.com

• If you use our work, you share the results under a similar licence

A full copy of the licence can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

You are welcome to ask for permission to use this work for purposes other than those covered by the licence.

We gratefully acknowledge the work of Creative Commons in inspiring our approach to copyright. To find out more go to www.creativecommons.org

The Consumer Duty at One Year – Can we have a more active and engaged view of consumers?

John Finch and Chuks Otioma draw on their research with the Financial Regulation Innovation Lab, arguing that the Duty would benefit from a clearer understanding of consumers being active, engaged and innovative

The UK Financial Conduct Authority held webinar at the end of July marking twelve months since introducing the Consumer Duty. The webinar provides a welcome opportunity to reflect on the ways in which the Duty has changed our understandings of financial products and services as consumers experience these. While there are antecedents to the Consumer Duty, and it exists alongside other regulations such as Advertising Standards and General Data Protection, the simple force of the term Consumer Duty is remarkable. The landscape is changed. Financial services providers have a duty to show how their products and services provide good quality outcomes for their consumers. We argue that the next steps for the Consumer Duty should embrace a more nuanced view of consumers as engaged, active, and co-developing, partners in innovation.

Outcomes-based regulation

The Consumer Duty is an example of outcomes regulation. In other words, regulation and corporate activity meet in compliance as much around how they have met performance expectations and have in place processes to continue to do so. The Consumer Duty sets out four dimensions or qualities of good outcomes for consumers: price and value, consumer understanding, consumer support, and governance of products and services. Additionally, providers should pay attention specifically to vulnerable consumers, that suppliers – often to include FinTechs – are included where having a material effect, and with the outcomes of understanding and support comes an implication for enhancing consumers’ financial literacy.

As engaged researchers, we have had an interesting year following the Consumer Duty. We have organised workshops internationally where researchers and practitioners have discussed their approaches. We also highlight presentations at the Market Research Society’s annual financial services research conference. The November 2023 meeting was particularly good. Fair4All Finance focussed on financial inclusion and the more effective uses of market segmentation techniques to draw out consumer experiences in enchaining financial inclusion (https://fair4allfinance.org.uk/segmentation/). Cowry Consulting reported on applying behavioural science to providers’ product service development in complex financial products, and in enhancing consumer understanding and support (https://2547826.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/2547826/On%20The%20Brain%20-%20ESG%20Edition.pdf).

Both these themes (segmentation in support of financial inclusion, and applications of behavioural science) speak to a need for a more thorough integration of consumers’ experiences and practices, of how they go about engaging with and using financial services products. As the FCA webinar highlighted, one source of data is complaints and resolution through the Financial Ombudsman. This vital work is though something of a last resort for consumers and providers where things could have gone wrong. Otherwise, drawing in consumers and understanding their experiences, is a longstanding challenge, reflected in stakeholder theory, regulation, and responsible innovation and science, of how to gather consumers and consumer practices into groups in a way that has some comparability with service providers.

Insights can be gained by catching some of the hints about consumers’ process and capabilities reflected into providers through principles of outcomes regulation. If we accept consumers and consumption as active, requiring capability, literacy, understanding subject to behavioural bias, contending with complexity, and varied across individual – even if proxied through segmenting – this rich experience should find a way into the Consumer Duty and our reflections of its implementation.

Active, engaged consumers

Let’s sketch this in a little more detail. Consumer Duty implies a rebalancing of power towards that age-old principle in economics of consumer sovereignty. This is not easily achieved. The Consumer Duty has four dimensions of good outcomes, and only one is price and value. So, as with many consumer activities, outcomes of Consumer Duty are not simply of consumption being a purchase then ‘value sink’. Consumers need to work hard to access the value designed into and intended in their financial products and services. Just as an example, and with relevance to FinTech too, financial inclusion is tensioned against the investments expected of consumers to participate in the market, in financial services, of a mobile phone with an up-to-date operating system and perhaps paid-for apps. Consumers co-invest and through their personalised adaptions in use, modify the digital infrastructure presumed for many financial services.

New technologies can support drawing insights from consumers. Leveraging AI solutions that provide capabilities for richer data, real time analysis and consumer insights, Fintech and financial service providers have a vantage potin from which to understand customer characteristics and preferences, engage with and offer personalised products that match consumer expectations. This way, financial products and services can extend beyond segmentation and stand a better chance to be directed towards good consumer outcomes. As a note of caution, sole deployment of cutting-edge technologies and data per se can narrow the scope for improved consumer experiences and good outcomes. This sounds the importance of business models that promote co-creation with consumers through product design, development and delivery that allow consumers to interact with and tinker around both products and services, and the platforms on which they are delivered.

Furthermore, consumers often make their own financial bundles and portfolios. With respect to financial inclusion and vulnerability, they do so with great ingenuity, in mind-occupying and time-consuming ways, through trial and error, shared experiences, and, crucially, cutting across providers and product categories. This can perhaps include juggling credit cards, short-term loans, welfare payments, and overdrafts. These are consumer experiences: innovative, imaginative, adaptive, ingenious, sometimes urgent and under pressure. Our challenge is to draw consumer experiences and actions into the view of the Consumer Duty. To vary our focus or unit of analysis to, of course, include individual products and services from providers, but also recognising the additional consumption activities among consumers, and how these vary significantly. This can also allow us to reflect on the definitions of, and contributions to, Consumer Duty categories of – taken together – price and value, consumer understanding, and consumer support. And such an approach can be part of and arguably improve the governance of products and services.

Professor John Finch and Dr Chuks Otioma are at the University of Glasgow’s Adam Smith Business School and the Financial Regulation Innovation Lab (a partnership between FinTech Scotland, University of Strathclyde, and University of Glasgow). We can be contact at john.finch@glasgow.ac.uk, and chuks.otioma@glasgow.ac.uk.

We acknowledge funding from Innovate UK, award 10055559.

Open Access. Some rights reserved.

Open Access. Some rights reserved. The publishers, the University of Glasgow and FinTech Scotland, and the authors, John Finch and Chuks Otioma, want to encourage the circulation of our work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. We therefore have an open access policy which enables anyone to access our content online without charge. Anyone can download, save, perform or distribute this work in any format, including translation, without written permission. This is subject to the terms of the Creative Commons By Share Alike licence. The main conditions are:

- The University of Glasgow, FinTech Scotland, and the authors are credited, including our web addresses www.gla.ac.uk, and www.fintechscotland.com

- If you use our work, you share the results under a similar licence

A full copy of the licence can be found at

You are welcome to ask for permission to use this work for purposes other than those covered by the licence.

We gratefully acknowledge the work of Creative Commons in inspiring our approach to copyright. To find out more go to www.creativecommons.org

AI and RegTech: Industry Insights on AI in Financial Regulation

Article written by Alessio Azzutti (University of Glasgow), Mark Cummins (University of Strathclyde),

Iain McNeil (University of Glasgow).

Note: Segments of this blog were generated by ChatGPT using notes taken on the day capturing the

presentations and discussions. The authors edited this generated content accordingly.

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into financial practice and regulatory processes represents a pivotal shift, promising enhanced efficiency, accuracy, and innovation across regulatory compliance and supervision. Our recent discussions explored various facets of AI’s role in financial regulation, revealing a landscape rich with opportunities and challenges. This synthesis (generated by ChatGPT from our discussions with industry partners in our AI & RegTech Workshop on 10 May 2024 and revised by the authors) aims to distill key insights from the discussion across themes, providing an overview of the promises that AI bears on regulatory practices. It will be followed soon by a white paper as part of the White Paper Series published by the Financial Regulation Innovation Lab. This white paper will set out the issues in more detail, linking them to prior research and evolving practice.

Transformation of Regulatory Compliance through AI

AI’s integration into regulatory compliance processes marks a significant evolution in how financial institutions deal with complex regulatory environments. Discussions highlighted AI’s potential to revolutionise compliance by automating and augmenting tasks such as data collection, management and analysis, especially in relation to vast datasets in order to generate actionable insights with unprecedented speed and accuracy. At the same time, the efficacy of AI in compliance hinges on several critical factors. Financial regulations encompass a spectrum of rules ranging from overarching principles to specific quantitative benchmarks and qualitative guidelines.

AI applications must move among these diverse regulatory requirements, which vary in complexity and scope across jurisdictions. Participants underscored the importance of regulatory clarity in fostering AI adoption in compliance (RegTech). Uncertainties about regulatory expectations can stifle innovation in RegTech solutions. Standardisation of data formats, communication protocols, and other AI-related requirements emerged as essential prerequisites to streamline AI integration and enhance compliance efficiency. AI can be integrated into compliance through comprehensive system-wide approaches or targeted solutions for specific regulatory challenges. In addressing the relationship between AI and the various layers of regulation, the roundtable emphasised the need to view compliance as a dynamic process and activity rather than a static framework.

Participants agreed on some crucial aspects related to AI governance. Despite AI’s capabilities, human oversight remains indispensable, for instance, to validate AI outputs, ensure ethical decision-making, and interpret regulatory requirements accurately. Indeed, the discussion highlighted the ongoing need for human experts to manage AI-augmented compliance effectively. Greater standardisation in AI-related technologies and regulatory frameworks are also seen as future catalysts for innovation in the RegTech sector. Standardised practices can enable financial institutions and technology providers to focus on enhancing their AI solutions rather than coping with disparate regulatory landscapes.

Design and Governance of AI-Enabled Compliance Systems

The application of AI, particularly its subfield of Machine Learning (ML) methods, in compliance systems was explored as a transformative force reshaping business strategies and operations within financial institutions. AI systems empower organisations to analyse complex datasets rapidly and derive insights that inform decision-making. Among other things, participants highlighted AI’s role in improving risk management, fraud detection, and overall operational efficiency. However, the design of AI systems in compliance is seen as extending beyond automation to facilitate strategic alignment with business goals and regulatory objectives.

In this context, ensuring effective model governance emerged as a critical priority for organisations deploying AI in regulatory compliance. Robust governance frameworks can help ensure transparency, accountability, and compliance with regulatory standards. The emerging field of Explainable AI (XAI) is deemed critical in financial services to ensure transparency and build trust among stakeholders. Clear explanations of AI processes and decisions enhance user confidence and facilitate regulatory compliance.

Addressing biases—whether in data, models, and their inherent human assumptions—was highlighted as essential to ensure fair outcomes and mitigate risks. Robust governance frameworks include mechanisms for bias detection, mitigation, and continuous monitoring to uphold ethical and legal standards. Discussions emphasised the need for clear policies and procedures to monitor AI models in and along the entire AI lifecycle.

Moreover, the debate between in-house AI development versus third-party vendor solutions highlighted some organisational preferences and challenges. Large financial institutions often opt for in-house development to tailor AI solutions to their specific needs and maintain control over data integrity and security.

Broadly speaking, legal and ethical considerations in AI deployment include data privacy, intellectual property rights, and liability for AI-based decisions. The roundtable discussions emphasised the need for clear regulatory frameworks to address all the complexities embedded in AI governance, which necessitates shared responsibility across stakeholders—developers, users, regulators, and consumers. Clear delineation of roles and responsibilities was deemed crucial by participants to mitigate risks and ensure responsible AI deployment.

The specific exploration of Generative AI in compliance identified its potential in automating routine tasks and enhancing productivity. Despite its benefits, concerns about data privacy, security, and the ethical implications of AI-generated content remain paramount. We heard further calls for human-in-the-loop solutions. Human oversight ensures the credibility and accuracy of Generative AI outputs.

Mutual Reinforcement of RegTech and SupTech

RegTech (regulatory technology) and SupTech (supervisory technology) represent two sides of the same coin, namely the adoption of innovative technology to bring greater effectiveness and efficiency to financial regulation and its enforcement. RegTech tools powered by AI enhance regulatory compliance by improving understanding of regulations, managing business activities, and achieving higher-quality compliance outcomes. However, regulatory fragmentation and differing compliance requirements pose challenges to widespread and trustworthy adoption. In parallel, financial supervisors are researching and gradually adopting AI-based SupTech solutions to enhance their ability to achieve supervisory objectives in an efficient and effective manner. Interoperability between RegTech and SupTech systems is essential for frictionless and secure data exchange between regulators/supervisors and regulated entities in order to improve regulatory oversight. Standardised data formats, communication protocols, and AI-related requirements promote collaboration between financial institutions and regulatory authorities. Greater regulatory clarity and standardisation are seen as catalysts for innovation in the RegTech space. Clear guidelines on regulatory requirements targeting AI applications facilitate technological advancements while ensuring compliance with regulatory standards. Collaboration between public authorities, financial institutions, and technology providers is expected to foster a conducive ecosystem for AI innovation in financial regulation. The roundtable discussions emphasised the importance of collaborative efforts to overcome regulatory challenges and promote technological convergence.

Conclusion