Consumers as Innovators and the UK Financial Conduct Authority’s Consumer Duty

We address the scope, purpose, and initial implementation from July 2023 of the UK Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA) Consumer Duty. As an instance of financial regulation innovation, the Consumer Duty is having a major impact in the financial services sector and has impacted on the organisation of markets for financial services and in the interactions of consumers and providers.

The Duty brings to prominence the ways in which the production, marketing and use of financial services products and services are strongly interrelated. It highlights: (1) Consumers’ financial literacy; (2) Providers’ confidence that their products and services and communications about these are being understood; and (3) How providers are anticipating and coping with vulnerability among their customers.

Together, these recognise consumers as being active, engaged, adaptive and innovative. We position the paper in terms of active consumption and market and marketing channels so as to focus on active consumers, and consumer vulnerability. To illustrate how the Consumer Duty is shaping the development, marketing and uses of financial services, we explore a sample of cases reported by the Financial Ombudsman Service, in which the issues referenced are akin to the elements addressed in the Consumer Duty.

We find that consumer understanding is a prominent factor, which also impacts on a number of other categories and subcategories. We also see, through the perspective of Consumer Duty, a somewhat pacified or pacifying view of consumers and in some instances, tensions emerging between consumer adaptations and the contractual terms for financial products and services. This adds to our conceptual framing of market channel and its implications for consumer vulnerability.

Navigating Double Materiality in ESG: Practical Steps for Businesses

Introduction to Double Materiality

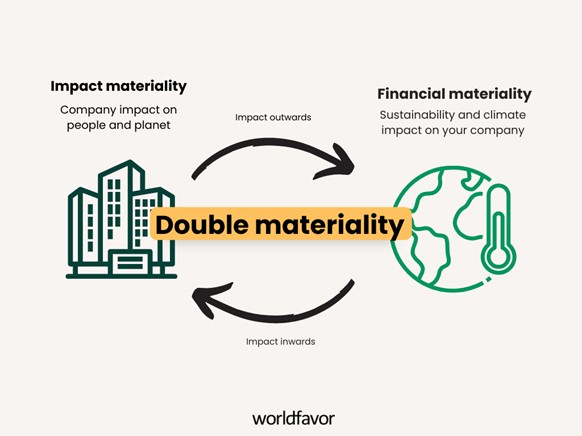

Double materiality emerged as a concept relatively recently, but has been gaining interest as a practical, actionable conceptualization of ESG outputs. Materiality itself traditionally focused on how a factor impacted firm financial performance, a decidedly unidirectional approach. Double materiality looks to identify both the financial materiality of an issue as well as the impact materiality, which assess the material impact upon society and the environment. Rising stakeholder demands and regulatory pressures are making double materiality more and more prevalent in today’s business climate. To practically navigate double materiality, companies must adopt comprehensive strategies that integrate both financial and societal/environmental dimensions into their decision-making processes.

The EU Commission’s Supplementary Directive 2013/34/EU states, “…double materiality as the basis for sustainability disclosures”. The two dimensions of double materiality, impact and financial, are further noted as being ‘…inter-related and the interdependencies between these two dimensions shall be considered” (section 3.3). This is best visualized in the following graphic:

Image credits: Worldfavor, July 2023

As shown, the assessment impact or financial materiality are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. The impacts are, from a company perspective, split between impact inwards and impact outwards, meaning the materiality of an issue as it impacts the company itself (impact inwards) and the material impact of a company’s actions on society and the environment (impact outwards). In today’s reporting climate, those two directions are seen as more closely related than ever before.

In industries such as Aerospace, the concept of materiality is closely linked to innovation. Companies like SpaceX, Orbex, or Collins Aerospace have defined themselves as organisations with a sustainability element. This is a clear demonstration of the circular nature of double materiality, in that the impact materiality (the firm’s sustainability efforts) are directly impacting the financial materiality (inwards impact in the form of sales and customers, outwards impact in the form of environmental innovation and positive social investment) and vice versa. For instance, when discussing potential environmental impacts of manufacturing for aerospace and defense technologies, S&P Global argued that the climate transition would be significantly material for stakeholders as manufacturing and transportation emissions require long-term strategic planning but is less likely to impact near-term credit (S&P Global, 2022).

In defining impacts, it is important to note that risk and opportunities are both components of impact, but that they are not necessarily the entirety of the impact. For instance, an environmental impact may become financially material due to changing weather patterns. Conversely, a financial issue may develop impact materiality through a change in regulations or soft law pressures.

Practical Steps for Businesses

To effectively navigate double materiality, businesses need to implement a series of practical steps, encompassing governance, stakeholder engagement, data collection, and reporting.

1. Establish Strong Governance Frameworks

Leadership and Oversight: Establish a governance framework that includes oversight by the board of directors or a dedicated ESG committee. This structure should ensure that double materiality is integrated into the company’s strategic objectives.

Roles and Responsibilities: Clearly define roles and responsibilities for ESG initiatives across various departments, with a defined company-wide strategy to ensure efficiency of data collection and reporting. Assign senior executives to oversee both financial and impact materiality aspects, ensuring alignment with the company’s overall strategy.

2. Engage Stakeholders

Identifying Stakeholders: Identify and actively engage with key stakeholders, including investors, employees, customers, suppliers, regulators, and local communities. Understanding their concerns and expectations is vital for addressing both financial and impact materiality.

Dialogue and Collaboration: Engage in open and continuous dialogue with stakeholders through surveys, meetings, and advisory panels. Collaboration with stakeholders helps in identifying material ESG issues that are relevant from both financial and impact perspectives.

3. Conduct Materiality Assessments

Materiality Matrix: Develop a materiality matrix that plots ESG issues based on their importance to stakeholders (impact materiality) and their potential financial impact on the company (financial materiality). This visual tool helps prioritize ESG issues that require attention.

Dynamic Assessments: Conduct regular materiality assessments to adapt to evolving ESG landscapes and stakeholder expectations. This ensures that the company remains responsive to new challenges and opportunities.

4. Integrate ESG into Risk Management

Risk Identification: Identify ESG-related risks that could affect the company’s financial performance and societal impact. This includes environmental risks (e.g., climate change), social risks (e.g., labor practices), and governance risks (e.g., corruption).

Risk Mitigation: Develop and implement strategies to mitigate identified risks. This might involve adopting sustainable practices, improving supply chain transparency, or enhancing corporate governance standards.

5. Develop Robust Data Collection and Reporting Mechanisms

Data Collection Systems: Implement robust data collection systems to gather accurate and reliable ESG data. Use technology solutions like IoT, blockchain, and AI to enhance data accuracy and transparency.

Reporting Standards: Align reporting with established frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), and Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). These frameworks provide guidelines for comprehensive and comparable ESG reporting.

Integrated Reporting: Consider adopting integrated reporting, which combines financial and ESG information into a single report. This approach provides a holistic view of the company’s performance and its impacts, enhancing transparency and accountability.

6. Foster a Culture of Sustainability

Employee Engagement: Educate and engage employees at all levels about the importance of double materiality and sustainable practices. Encourage employees to contribute ideas and initiatives that promote sustainability.

Incentives and Recognition: Establish incentive programs to reward employees for their contributions to ESG goals. Recognize and celebrate achievements in sustainability to reinforce the company’s commitment to double materiality.

Challenges and Solutions

Data Complexity

In speaking to any ESG practitioner, one of the first challenges to arise is data collection. The data itself is often spread throughout a company, does not fit neatly into easily-organised spreadsheets, or may be difficult to understand in differing contexts (i.e. data from suppliers regarding their carbon emissions may not be shared in the format required by reporting standards).

To address this, companies can invest in advanced data management tools, third party support or automation systems, and design internal systems for data collection. It will be an investment of time and personnel but is also likely to be regulated and required in the near future.

Stakeholder Alignment

Particularly in industries with heavy manufacturing or extractive practices, it may be difficult to align stakeholder interests in a manner that is socially and environmentally material, without sacrificing financial performance. Engaging with stakeholders and third-party expertise while seeking innovative solutions and long-term strategic planning allows companies to effectively address ESG concerns.

Conclusion

Navigating double materiality requires a strategic and integrated approach that aligns financial performance with societal and environmental impacts. By establishing robust governance frameworks, actively engaging stakeholders, conducting dynamic materiality assessments, integrating ESG into risk management, developing comprehensive reporting mechanisms, and fostering a culture of sustainability, companies can effectively integrate double materiality. Success in this area not only enhances corporate reputation and stakeholder trust but also drives long-term value creation in an increasingly sustainability-focused world.

Resources

Boeke, E., York, B. N., London, D. M., Tsocanos, B., York, N., & Paris, P. G. (2022). Sustainable Finance Credit Ratings ESG Materiality Map Aerospace And Defense.

Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772 of 31 July 2023 supplementing Directive 2013/34/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards sustainability reporting standards, (2023).

Sean Michael Kerner. (2024, April). Double Materiality. Https://Www.Techtarget.Com/Whatis/Definition/Double-Materiality#:~:Text=Double%20materiality%20acknowledges%20risks%20and,Environment%20and%20society%20at%20large.

S&P Global. (n.d.). Materiality Mapping: Providing Insights Into The Relative Materiality Of ESG Factors https://www.spglobal.com/esg/insights/featured/special-editorial/materiality-mapping-providing-insights-into-the-relative-materiality-of-esg-factors

Worldfavor. (2023, July). CSRD: what is the double materiality assessment? Https://Blog.Worldfavor.Com/Csrd-What-Is-the-Double-Materiality-Assessment.

Erika Anderson’s work has focused on ESG and sustainability in the tech and finance space for the better part of a decade. In working closely with industry partners, she focuses primarily on issues of sustainable finance, social and environmental intersections, and actionable research for strategic ESG implementation. She also serves as Co-Founder of the Guam Human Rights Initiative, a collaborative research nonprofit focused on human rights issues on Guam and throughout the Pacific.

The European Sustainability Reporting Standards and Opportunities for Financial Services

This white paper introduces the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), which underpin the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD); a core component of the EU’s Sustainable Finance Framework. It introduces the key concepts of the standards, and breaks down the disclosure requirements of cross-cutting and topical standards, such as biodiversity and ecosystems so that:

1. Corporations have a better understanding of what they must produce to adhere to the standards; and

2. Financial Services have a better understanding of what metrics they will have available to them to better assess risk, develop new financial products and ease their own disclosure requirement burden, through a direct mapping of the ESRS-SFDR only datapoints provided in Annex A.

3. Prepares the reader for the data mapping of White Paper 3: Mapping ESRS Disclosure Datapoints to Relevant Datasets in the series, where specific topics and datapoints are mapped directly to relevant datasets that can be used as part of their analysis.

A key learning is that the ESRS disclosures will be provided in digitally tagged format, eXtensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL), simplifying reporting and presenting new opportunities across the Financial Services sector, such as enhanced investment analysis, including aggregation of sector/country level data and automated analysis, or integration into traditional analysis workflows.

The EU Green Deal and the Sustainable Finance Framework

This white paper is the first in a set exploring the use of geospatial data in Environmental,Social and Governance (ESG) regulations. This first paper introduces the EU’s Green Deal and Sustainable Finance Framework to set the scene for exploring the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) in detail.

The ESRS are a focal point as they are the most substantial and, importantly, first mandatory sustainability standards that demand a double materiality approach. This requires a joint assessment of the impact the corporation is having on the environment and society, and the financial risks and opportunities that sustainability factors are having on the corporation. Simply put, if you adhere to the ESRS, then you are likely to satisfy other sustainability standards or frameworks.

The ESRS are a foundational element of the Corporate Sustainability Responsibility Directive (CSRD), the Sustainable Finance Reporting Directive (SFDR) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), which together contribute to the EU’s Sustainable Finance Framework. These are mandatory directives within the EU and present the first opportunity to assess corporations on a level playing field using double materiality. The aim of this set of white papers is to present the reader with information to:

a. Understand the EU sustainability landscape, and its place within the international sustainability landscape;

b. Demonstrate the link between corporate reporting and sustainable finance, by discussing the relationship between the CSRD, SFDR and CSDDD;

c. Identify the opportunities within Financial Services due to the introduction of mandatory standards using double materiality, specifically the ESRS;

d. Demonstrate how geospatial data can be used to aid the disclosure requirements of the ESRS.

Navigating Regulatory Risk Trends in 2025: Key Insights from Pinsent Masons

As we step into 2025, the financial services landscape faces a year of transformation, with regulators aiming to balance economic growth with robust consumer protection. In the latest edition of Pinsent Masons’ Financial Services Regulatory Risk Trends update, our strategic partner focusses on critical regulatory developments shaping the industry.

The Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA) recently released a five-year strategy with a clear focus on resilience—both for consumers and financial institutions. This edition of Financial Services Regulatory Risk Trends explores the key regulatory shifts that firms should be aware of, particularly in relation to consumer and operational resilience.

Consumer Resilience: A Stronger Framework for Protection

The UK Government’s recent Call for Input on closer collaboration between the FCA and the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS) marks a significant development in consumer protection. This initiative comes at a time when mass redress events—such as undisclosed motor finance commissions—are drawing considerable attention from both regulators and courts.

Additionally, firms must navigate the FCA’s evolving stance on the advice/guidance boundary and targeted consumer support, especially in light of rising customer complaints and the continued embedding of the Consumer Duty framework.

Operational Resilience: Strengthening Financial Infrastructure

Beyond consumer-focused regulation, 2025 will also see increased scrutiny of ‘critical third parties’—a move that introduces further regulatory requirements for firms reliant on outsourced services. These new measures will likely reshape the contractual landscape between financial institutions and their key service providers, reinforcing the need for robust operational resilience strategies.

Sector-Specific Interventions: Motor Insurance and Capital Markets in Focus

The motor insurance market is set for a period of regulatory intervention, with the launch of a competition market study and the establishment of a motor insurance taskforce. These initiatives aim to address concerns surrounding fair pricing and market competition.

Meanwhile, capital markets also face transformation with the arrival of PISCES, a new trading platform set to modernise the sector and enhance market efficiency. With regulators seeking to foster competitiveness while upholding market integrity, firms should anticipate further updates in this space.

Read the full report here.

Systems in the Making: the Role of Companies in Implementing Sustainability Policy and Reporting

This paper focuses on the implementation of corporate sustainability, or Environment, Social and Governance, reporting. The introduction from 2023 of mandatory reporting is a key milestone in sustainability.

Adopting a comparative case method, we identify as related case studies Materiality (in reporting), Transition (in corporate strategy), and Stewardship (in fund management). We compare these by applying the theory-led themes of system openness, the agency or power of coalitions in producing and acting upon reports, contests in the qualification of key data, and through business exchanges related to or enabled by sustainability reports.

Drawing on a two-year applied project, we elaborate upon policy, regulation, business and industrial markets, and business relationships. We find that Materiality is the most stable and well-framed system. It produces key outcomes in depicting a reporting company’s sustainability risks and opportunities. Transition is the most open, influenced by global and jurisdiction task forces, for example tasked with achieving net zero policy obligations.

Stewardship in the UK articulates a set of principles, which guide fund managers in engaging with investee companies. We conclude that sustainability policy is at the same time setting in progress the forming of three systems, corresponding to this paper’s three case studies. Each has its own development, function and sets of facts, though each is beginning to achieve its function through interactions and exchanges with the other two.

Promoting Fairness and Exploring Algorithmic Discrimination in Financial Decision Making Through Explainable Artificial Intelligence

In this white paper a comprehensive toolbox is developed, grounded in an ethical “rights to

explanation” framework, deploying state-of-the-art machine learning/artificial intelligence models,

through the lens of explainability.

Harnessing these explainable artificial intelligence algorithms within the toolbox, we propose implementing an ensemble of model-agnostic techniques, to improve fairness in financial decision making, with a particular focus on US home mortgage loan applications with a granular public dataset.

We also highlight variability in these techniques, imposing various pragmatic scenarios that explore real-world decision making, alongside equality of opportunity and equality of outcome conditions. We highlight potential pitfalls, nuances, and possible innovations in applying these techniques, while providing the ability to simultaneously assess the impact of any specific variable in decision making, and a model’s performance in such decision making, with established machine learning criteria.

Furthermore, we showcase the trade-off between fairness and model performance optimization with a protected characteristic (age) that might form the basis of plausibly discriminatory practices in such a context. Our study aims to be in the spirit of Agarwal, Muckley, & Neelakantan (2023), Kelley, Ovchinnikov, Hardoon, & Heinrich, (2022), Kozodoi, Jacob, & Lessmann (2022), and Kim & Routledge (2022), among others. We lastly identify areas for future research.

Fairness and Discrimination in Lending Decisions: Multiple Protected Characteristics Analysis

We build upon the comprehensive toolbox developed in Jain, Bowden and Cummins

(2024), extending its applicability to multiple protected characteristics.

We explore a way in which several characteristics can be simultaneously considered for multi-dimensional fairness promotion and potential mitigation of plausibly discriminatory practices. In the spirit of Jain, Bowden and Cummins (2024), once again we do this with a particular focus on US home

mortgage loan applications with a granular public dataset.

Finally, we address a prior deficiency, namely a worse overall model accuracy/performance as measured by Area Under the Curve (AUC). The improved AUC can be attributed to a better True Positive Rate of correctly classified loan acceptances, which is achieved with the aid of hyperparameter tuning.

Specifically, we use Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation combined with overfitting- robust hyperparameter tuning facilitated with the aid of a Grid Search. These were discussed but not explicitly implemented in the use case of Jain, Bowden and Cummins (2024). We document that even a narrow set and range of hyperparameters (mitigating the computational cost of employing the Grid Search) is sufficient to elicit these improvements.

Lastly, we provide recommendations on the implications of our results including where a

human-in-the-loop

Enhancing Financial Crime Detection By Implementing End-to-end AI Frameworks

Economic crime, encompassing money laundering, fraud, scams, and various other

illegal financial activities, continues to evolve with the emergence of sophisticated Artificial

Intelligence (AI) technologies.

This white paper explores the dual-edged nature of AI in the financial sector. While AI tools are increasingly being exploited by criminals to commit financial crimes, they also hold the key to more robust and effective detection and prevention strategies.

This paper delves into the array of AI techniques currently leveraged by malicious criminals, including deepfake technologies, phishing and spear phishing, automated social engineering, credential stuffing, synthetic identity fraud and others.

Furthermore, it provides a comprehensive analysis of AI techniques capable of countering

these threats. Key focus areas include Neural Networks for unusual patterns and behaviours,

gradient boosting algorithms for risk assessment, reinforcement learning for optimisation of

decision making, Markov chains for temporal patterns and anomalies over time, Naïve Bayes

for real-time classification and decision trees for interpretable detection.

The culmination of this paper is the presentation of a state-of-the-art end-to-end AI-driven solution that integrates AI technology to offer a holistic and dynamically adaptable approach to financial crime detection and prevention. By implementing this framework, financial institutions can significantly enhance their capabilities to identify, mitigate, and prevent financial crimes, ensuring a more secure financial ecosystem.

Using Automation and AI toCombat Money Laundering

Money laundering, which is the criminal activity of processing criminal proceeds to disguise their origin is one of the gravest problems faced by the global economy, and its size is growing rapidly. It is estimated that 2- 5% of the global GDP or US$800 billion to US$2 trillion is being laundered every year across the globe.

Banks have begun to understand that their legacy rules-based systems cannot effectively mitigate risks related to money laundering. There is a need to embrace advanced technology that can effectively solve their problems of getting involved in money laundering cases. This white paper outlines a case study focusing on the effectiveness and limitations of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in detecting and preventing money laundering activities. It will provide an overview of the design, architecture, implementation, and testing of such a strategy.